During the past two weeks, the U.S. poultry industry lost 188,000 turkeys and breeders in seven outbreaks in three states. The egg segment lost a total of 1.7 million hens in two outbreaks in California and Iowa. Since the onset of fall 2023, USDA has depopulated close to six million egg production hens together with at-risk pullets, 1.5 million broilers and breeders, 2.7 million turkeys and breeders and 600,000 other commercial species. This dismal record presumes a repeat of 2022 that was devastating to turkey and layer producers, the public sector and above all, for consumers.

From informal and anonymous conversations with middle-level APHIS professionals, it is apparent that senior administrators are committed to a perpetual cycle of diagnosis, depopulation and surveillance over the long-term. If we knew more about how infection is actually introduced onto farms, we would be in a better position to protect flocks. The delayed and incomplete epidemiologic studies on 2022 cases with reports delayed by a year have not helped in identifying factors leading to outbreaks on farms and complexes. In the absence of an understanding of how avian influenza virus travels from the cloacas of migratory waterfowl to the nares of confined hens we are unable to implement definitive action to reduce the incidence rate. It is self-evident and confirmed by preliminary studies that proximity of migratory waterfowl and possibly infected domestic birds to farms represents a risk factor. This is supported by surveys confirming shedding of H5N1 avian influenza virus. It is also evident that specific counties in Minnesota, Iowa, Colorado, Wisconsin, North Dakota and South Dakota among others are vulnerable to both infection and reinfection due to their proximity to wetlands and expanses of water that attract migratory waterfowl.

Admittedly, conceptual biosecurity is compromised by locating vulnerable poultry flocks in flyways that place them in contact with shedders of virus. There are evidently deficiencies in both structural and operational biosecurity over and above the basic flaw of location represented by conceptual biosecurity. The USDA continually promotes generic biosecurity in general terms without identifying specific deficiencies in any of the installations or procedures that have contributed to infection of commercial flocks. Factors including feed supplied from common mills, especially in the turkey segment and obvious deviations from high levels of operational biosecurity have probably contributed to outbreaks. In specific cases during 2022, some large egg production complexes were inexplicably impacted. These farms were known to exercise extreme levels of biosecurity and with anecdotal evidence of airborne transmission of virus. This route of infection may have extended for distances of up to a mile but most likely was measured in hundreds of yards between the perimeters of farms and adjacent waste lagoons or wetlands colonized by migratory birds.

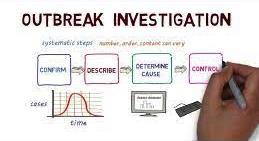

EGG-NEWS has consistently and repeatedly urged APHIS to mount an intensive epidemiologic evaluation of risk factors contributing to outbreaks. Surely experience in 2015 should have predicated preemptive planning for investigations in anticipation of a likely series of future outbreaks. These occurred in 2022 with continuation through the present year and with the prospect of seasonal continuation through 2024. What is needed is to immediate deploy a team of trained personnel to investigate outbreaks as they occur. Epidemiologists conversant with practices used in both the egg and turkey industries should be sent to selected farms immediately a diagnosis is confirmed. Appropriate questionnaires should be developed that relate specifically to turkey and egg production units respectively. Recollection by managers and possible recognition of factors contributing to infection would be obtained reliably in real time. Attempting to identify risk factors months after an event using a generic 20-page questionnaire administered by telephone is an exercise in futility.

Evaluation of airborne transmission of H5N1 virus should be undertaken over the 2-to-5-day period required to depopulate a one million-hen or larger egg production complex. We need to know the level of airborne virus in the vicinity of concentrations of waterfowl that are congregating in high-risk counties in the states that have been seriously impacted. We need to know the duration of persistence of infectivity of virus excreted by waterfowl. We need to understand the effect of weather conditions including temperature, humidity, wind velocity and direction in relation to outbreaks. We need to establish factors contributing to vulnerability including the apparent high incidence rate among in-line or hybrid breaking operations.

APHIS can draw on hundreds of millions of dollars for depopulation, indemnity and cleanup. Surely, money should be made available to investigate why and how farms are infected with avian influenza? Colleagues in APHIS have both the desire and the ability to conduct structured epidemiologic investigations as a Departmental initiative especially in collaboration with specialists at Land Grant Universities in the states that are most affected. To date, many field veterinarians are functioning with minimal incentive and negligible support from their superiors. Allocation of funds to study why and how farms are infected in both the turkey and egg production sectors of the industry will be critical to developing future strategy for prevention.

There is a growing sentiment both within APHIS and the industry that if in fact avian influenza virus is introduced onto farms by the airborne route, then even the most intensive and efficient biosecurity will not be protective. Are we emulating the Aztecs by figuratively throwing virgins into a volcano to ensure its quiescence by analogy adhering slavishly to isolated aspects of biosecurity but ignoring the most important mechanism of infection? APHIS administrators are both intelligent and educated and must have considered airborne transmission as has been proven for Newcastle disease. Paramyxoviruses and orthomyxoviruses are not that different in their ability to survive in the environment and should have similar routes of transmission.

As noted in weekly postings, EGG-NEWS urges APHIS administrators to allocate resources to conduct epidemiologic investigations to be conducted in real time, with rapid analysis in order to provide the industry with practical and applicable procedures to protect flocks.

Unfortunately, if it is demonstrated that airborne transmission is a reality, and that even extreme biosecurity fails to provide absolute protection then additional protective modalities will be required. Regional, seasonal and segment-specific immunization emerges as a rational and potentially effective method of prevention. Vaccination as an adjunct to existing measures to protect flocks must lose its taint of heresy and undergo dispassionate scientific and economic evaluation based on sound epidemiologic investigations.