Europe is leading the way in developing, investigating and evaluating deployment of vaccines to control avian influenza. France will initiate a program mid-year as a response to unsuccessful eradication activities conducted almost annually. Expenditure in France was close to $1.5 billion for compensation and control in 2022.

Field evaluation of vaccines is in progress in the Netherlands, Italy, and Hungary involving the major segments of poultry production.

The European Union has accepted the principle of vaccination that will apply to 27 member nations. In accordance with recent decisions, vaccinated poultry, their products and day-old chicks can move freely within the EU effective March 2023. The Russian Union of Poultry Producers has evolved a strategy to administer vaccines against HPAI as an additional measure to control and prevent infections. Their decision was based on the need to maintain food security in the face of sanctions. But also in the realization that biosecurity alone was unable to interdict aerogenous spread of virus

The European Union has accepted the principle of vaccination that will apply to 27 member nations. In accordance with recent decisions, vaccinated poultry, their products and day-old chicks can move freely within the EU effective March 2023. The Russian Union of Poultry Producers has evolved a strategy to administer vaccines against HPAI as an additional measure to control and prevent infections. Their decision was based on the need to maintain food security in the face of sanctions. But also in the realization that biosecurity alone was unable to interdict aerogenous spread of virus

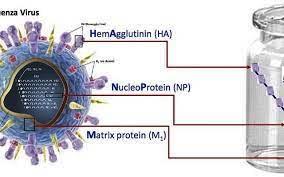

A variety of vaccines are now available with technology superseding the previously deployed hemagglutinin-specific, inactivated oil-emulsion vaccines. Biopharmaceutical manufacturers are now applying rHVT vector and mRNA technology for a new generation of vaccines. Commercially available rHVT vectored vaccines have been used successfully for a number of years in some countries in Asia, the Middle-East and in Mexico. They will be deployed in some South American nations including Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador currently experiencing outbreaks of HPAI.

A variety of vaccines are now available with technology superseding the previously deployed hemagglutinin-specific, inactivated oil-emulsion vaccines. Biopharmaceutical manufacturers are now applying rHVT vector and mRNA technology for a new generation of vaccines. Commercially available rHVT vectored vaccines have been used successfully for a number of years in some countries in Asia, the Middle-East and in Mexico. They will be deployed in some South American nations including Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador currently experiencing outbreaks of HPAI.

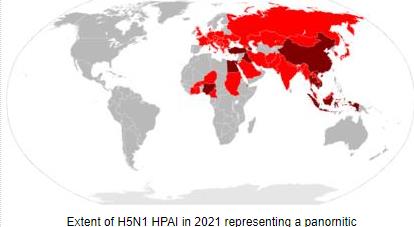

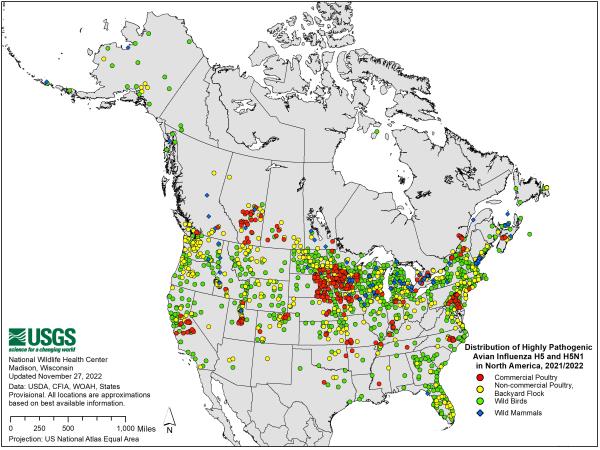

Opposition to vaccination against avian influenza is waning as nations realize that the H5N1 panornitic is not abating and that both migratory and domestic wild birds are both susceptible and are disseminating virus. The decision to implement vaccination as a component of a national control program follows the recognition that H5N1 HPAI is endemic in a nation or region. The fact that the virus has been identified in 47 states of the U.S., has required the depopulation of 57 million commercial birds including 10 million turkeys and 44 million laying hens and that sporadic outbreaks have persisted for over a year suggests that the infection can no longer be regarded as exotic and is de facto seasonally and regionally endemic.

Opposition to vaccination against avian influenza is waning as nations realize that the H5N1 panornitic is not abating and that both migratory and domestic wild birds are both susceptible and are disseminating virus. The decision to implement vaccination as a component of a national control program follows the recognition that H5N1 HPAI is endemic in a nation or region. The fact that the virus has been identified in 47 states of the U.S., has required the depopulation of 57 million commercial birds including 10 million turkeys and 44 million laying hens and that sporadic outbreaks have persisted for over a year suggests that the infection can no longer be regarded as exotic and is de facto seasonally and regionally endemic.

A major objection to vaccination is that immunized flocks may excrete virus if infected without an apparent clinical response. This is an obvious but surmountable obstacle. Shedding of virus is limited to about two weeks during which flocks can be quarantined. The complaint that vaccination will create a problem through differentiating vaccinated flocks from those that are infected is now spurious. Apart from the application of DIVA vaccines, the status of any flock can be established rapidly using PCR antigen detection. It is possible to certify that any flock or complex producing eggs or poultry meat is HPAI-negative based on PCR assay on the day before processing or packing. Export of poultry products will in future be based on acceptance of WOAH principles relating to regionalization for commercial shipments in addition to compartmentalization for eggs and day-old chicks.

|

It is ironic that nations including China and South Africa that have placed HPAI-related barriers against importation from entire states in the U.S. have infected flocks in their own countries. This is contrary to the trade regulations of the World Organization for Animal Health.

It is axiomatic that it is almost impossible and ultimately extremely expensive to eradicate an endemic disease, especially when the pathogen is constantly introduced by migratory birds. It should be accepted that avian influenza is in effect “the Newcastle disease of the 2020’s”. This catastrophic infection was effectively controlled and is no longer a restraint to commercial production as a result of extensive and effective immunization, despite the absence of durable biosecurity in many nations.

almost impossible and ultimately extremely expensive to eradicate an endemic disease, especially when the pathogen is constantly introduced by migratory birds. It should be accepted that avian influenza is in effect “the Newcastle disease of the 2020’s”. This catastrophic infection was effectively controlled and is no longer a restraint to commercial production as a result of extensive and effective immunization, despite the absence of durable biosecurity in many nations.

The problem of implementing a vaccination program against avian influenza in the U.S. is not the availability of effective vaccines. The restraint lies in intransigence among veterinary service administrators who are following a playbook antedating the 1984 outbreaks in Pennsylvania. Collectively they have failed to recognize the differences in the epidemiology of the current epornitic of H5N1 avian influenza and the growth of the industry since the outbreaks of H5N2 HPAI, four decades ago. Obstructing vaccination by delaying approval of vaccines that are used effectively in other nations, adherence to the export bogy and inappropriate interpretation of science to maintain a business-as-usual approach will not ultimately prevent vaccination.

The problem of implementing a vaccination program against avian influenza in the U.S. is not the availability of effective vaccines. The restraint lies in intransigence among veterinary service administrators who are following a playbook antedating the 1984 outbreaks in Pennsylvania. Collectively they have failed to recognize the differences in the epidemiology of the current epornitic of H5N1 avian influenza and the growth of the industry since the outbreaks of H5N2 HPAI, four decades ago. Obstructing vaccination by delaying approval of vaccines that are used effectively in other nations, adherence to the export bogy and inappropriate interpretation of science to maintain a business-as-usual approach will not ultimately prevent vaccination.

Based on the cost to the public and private sectors and to consumers, the U.S., Congress will likely turn off the compensation spigot and force adoption of vaccination.

Public health authorities will react aggressively if and when transmission to human contacts of infected poultry occurs. This is predicated on the wide range of terrestrial and aquatic mammals that are apparently susceptible to and die following exposure to H5N1 AIV. Infection is acquired from predation or from the environment and then spread intra- and inter-species.

Public health authorities will react aggressively if and when transmission to human contacts of infected poultry occurs. This is predicated on the wide range of terrestrial and aquatic mammals that are apparently susceptible to and die following exposure to H5N1 AIV. Infection is acquired from predation or from the environment and then spread intra- and inter-species.

Opposition to mass depopulation is gathering force and is generating opposition among average consumers. As we move into Spring with the prospect of an upsurge in avian cases it must be recognized that the HPAI situation has expanded from a veterinary problem to encompass the economy and public health considerations. Vaccination cannot continue to be ignored as a component of control and suppression of HPAI in the World and the U.S.