EGG-NEWS has advocated for limited application of vaccination as an adjunct to biosecurity since mid-2022. The series of postings regarding diagnosis, control and prevention of avian influenza can be retrieved by entering “avian influenza” and "HPAI vaccination” in the SEARCH block

The fault lines dividing protagonists of vaccination against highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) and those against this modality were evident at the UEP Committee briefing on January 24th and in hallways and show booths during the IPPE. The overwhelming sentiment within the egg production and turkey segments of the U. S. poultry industry is in favor of some application of vaccination as a supplement to existing control measures. The broiler industry is opposed to vaccination based on the perceived impact on trade, since close to sixteen percent of RTC voume produced in 2014 will be exported.

The epornitic of 2022/5 is not a repetition of 2015. The realities are:-

The epornitic of 2022/5 is not a repetition of 2015. The realities are:-

- The H5N1 strain with Eurasian genes is now a panornitic strain present in the E.U., Asia, and the Americas with Brazil, thus far, the only major poultry producing nation unaffected. Both Australia and New Zealand are at this time, free of infection due to remoteness from migratory flyways.

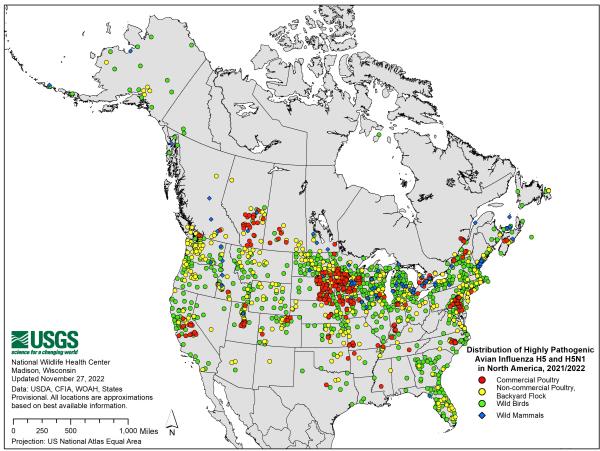

- Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza strain H5N1 is considered by many poultry health professionals to be de facto endemic in the U. S. This opinion is based on the infection having been diagnosed on commercial farms in more than 35 states, has required the depopulation of 56 million birds to date, is affecting both commercial and backyard flocks and has continued for twelve months. This scorecard is inconsistent with an exotic infection. Currently, many species of both migratory waterfowl and domestic birds show clinical signs and high mortality unlike previous H5 and H7 strains affecting only domestic poultry.

- The infection is regularly isolated from free-living mammals, including foxes, skunks, mink, bears, seals and a walrus. The limited surveillance of wildlife has provided inadequate confirmation of the extent of infection and the range of species involved.

- There is adequate anecdotal evidence to suggest that the disease can be transmitted over relatively short distances by the aerogenous route, thereby reducing the ability of commercial poultry producers to prevent infection through conventional biosecurity procedures.

It is an axiom that Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza is the Newcastle disease of the 2020s. During the 1960s and 1970s, velogenic viscerotropic Newcastle disease (vvND) was a catastrophic infection limiting production in intensive poultry industries in the E.U., Asia and Africa. This commentator observed the futile attempts of the Department of Agriculture to stamp-out what was evidently an endemic disease in the Republic of South Africa. When the Government ran out of money, resources and patience, and allowed vaccination, the industry responded by effectively suppressing the infection and restoring both production and profitability.

From comments provided by Julian Madeley, CEO of International Egg Commission, it is obvious that E.U. nations have recognized that HPAI H5N1 is endemic and are moving forward with adoption of vaccination as a component of their control programs. Stamping-out has proven to be ineffective, especially with free-range flocks as in France. Cynically it can be stated that this nation has successfully eradicated HPAI but on a successive annual basis over a number of years.

Dr. David Swayne recently organized an international conference on the application of HPAI vaccine. He emphasized the advantages of vaccination as an additional “layer of protection”. Establishing immunized populations in specific areas reduces the outbreak threshold for a given disease and reduces the financial impact when combined with traditional measures including depletion of affected flocks, quarantine and surveillance activities. Research conducted both at major universities and institutes worldwide and by the bio-pharmaceutics industry have provided a portfolio of vaccines that can be applied to specific types and ages of commercial poultry.

Dr. John Clifford, Veterinary Trade Policy Advisor to the USAPEEC and formerly Chief Veterinary Officer for the USDA, noted the difficulties associated with preventing infection applying current biosecurity practices. He highlighted the administrative restraints to vaccination that are based on the false premise that HPAI H5N1 is exotic and therefore can be eradicated. It is obvious that USDA-APHIS is using a playbook based on the1984 Pennsylvania epornitic that was self-limiting. In the absence of epidemiologic investigations that have been urged by state poultry associations and promoted by EGG-NEWS, APHIS continues to expend funds provided by their presumably bottomless piggybank, the Commodity Credit Corporation.

The contention expressed by a Senior Staff Veterinarian In The Poultry Health Strategy and Policy component of USDA-APHIS that the cost of a surveillance program would be as expensive as the cost of depopulation is fallacious and intended to support business-as-usual. Not only have the private and the public sector experienced losses as a result of HPAI, consumers have had to pay considerably more for eggs and turkey meat. If as is inevitable, infection moves into the broiler segment, HPAI will represent an even greater liability to the economy.

The concerns expressed by the broiler industry regarding trade have current validity. It would be possible, as Dr. Clifford noted, for changes to be effected in current U.S. policy to allow for limited and controlled vaccination. Nations importing leg quarters from the U. S. have in large measure endemic HPAI in their own industries or subsistence flocks. There is no specific ban on trade if a nation vaccinates according to World Organization for Animal Health regulations, providing that surveillance is maintained. It would be possible for states to certify that a specific complexe or flocks are free of HPAI by applying PCR prior to export of a consignment. The obstacles to introducing vaccination as an adjunct to limited depopulation are more institutional than scientific. Administrators of the USDA-APHIS have pursued a policy of “stamping out” a supposedly exotic disease without accepting the reality that HPAI is a panornitic infection and is de facto endemic in the U.S. After 50 million plus birds depopulated over a year without achieving eradication, it is difficult for any government agency to admit that they were wrong and accept a change in the approach to control.

|

Once the attitudinal block is resolved, programs to introduce vaccination on the basis of priorities can proceed. Breeder flocks and long-lived birds including egg-producing hens should be vaccinated. Flocks raised in areas of high population density especially with a history of HPAI could then be considered for protection. Some areas of the nation would remain susceptible based on a low probability of exposure. At the end of the day, scientific fact and sound principles of epidemiology should prevail. Effective vaccination will clearly reduce transmission between farms located in close proximity and will reduce replication of the virus both of which are, in fact, the justification for depopulation.

An unspoken component of the current debate over control of HPAI relates to the emergence of a strain of pandemic significance to human populations. The fact that H5N1 appears to have adapted to mammals should serve as a warning. Given enough susceptible birds or free-living mammals or for that matter, farmed mink in close association, over time, it is highly likely that a mutation may occur that not only results in infection of human contacts but may evolve to allow human-to-human transmission. The quicker that HPAI can be suppressed, but not necessarily eradicated in the short term, the greater will be the benefits to the poultry industries of the world and humanity. Vaccination against HPAI must be adopted as a valid consideration in control programs otherwise we will stumble on destroying flocks at great expense with consequential losses to producers and consumers.