The Montana State Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks recently announced that three immature grizzly bears in separate locations were euthanized as a result of infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. The bears demonstrated neurologic signs including disorientation and partial blindness resulting in starvation. Highly pathogenic avian influenza has been described in a skunk and fox in Montana during 2022 and has been diagnosed in raccoons, black bears and a coyote in other states. HPAI was diagnosed in a bear in Quebec in 2022 and has been isolated from marine mammals along the coast of Maine, the Canadian Maritimes and in Norway.

The Montana State Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks recently announced that three immature grizzly bears in separate locations were euthanized as a result of infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. The bears demonstrated neurologic signs including disorientation and partial blindness resulting in starvation. Highly pathogenic avian influenza has been described in a skunk and fox in Montana during 2022 and has been diagnosed in raccoons, black bears and a coyote in other states. HPAI was diagnosed in a bear in Quebec in 2022 and has been isolated from marine mammals along the coast of Maine, the Canadian Maritimes and in Norway.

Identifying an emergent pathogen such as Avian Influenza in wild mammals is difficult, given scavenging and destruction of carcasses. Dr. Jennifer Ramsey, Wildlife Veterinarian for the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, stated, “When you get that first detection you tend to start looking harder and you are more likely to find new cases.” She added “While it is unknown just how prevalent the virus is in wild birds, we know that it is active basically across the entire state due to the wide distribution of cases of HPAI mortality in some species of wild birds.”

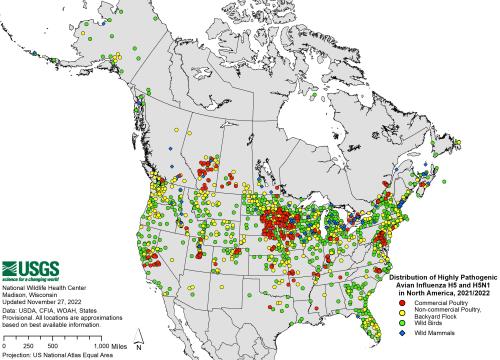

35 states, 12 months, 44 million hens, wild domestic birds and wildlife. Suggests HPAI is endemic |

Traditionally, USDA surveillance for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza is largely concentrated on hunter-killed waterfowl that serve as an early warning system for the presence of virus in an area. Given the widespread occurrence of H5N1 HPAI in backyard farms and reports of mortality in other than waterfowl and shore birds, it is most probable that the pathogen has now adapted to a wide range of domestic birds. This represents a heightened risk of introduction of infection onto commercial farms by direct contact or even by the aerogenous route. Evidence of widespread HPAI in wild bird populations as predicated by mortality and isolation of the virus from raptors, corvids and other species presumes endemnicity of the infection in regions of the U.S. This is borne out by ongoing cases in backyard flocks and commercial farms, unlike the previous 2015 and 1984 epornitics that reflected migration of waterfowl. Presence of the virus in 35 states and outbreaks extending over 12 months belies the contention that HPAI is an exotic infection. Accordingly attempts by the USDA-APHIS to control the disease by a traditional approach involving depopulation and disposal of infected flocks and surveillance will ultimately be futile. Other modalities including immunization as applied in other nations should be considered for incorporated into programs to control and prevent HPAI.